Brent Watanabe's San Andreas Deer Cam (2016) was screened in NEW DIRECTIONS on May 25 2016 in Milan, Italy, as part of GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY. In this exclusive interview, Watanabe discusses the creative process behind his unique project.

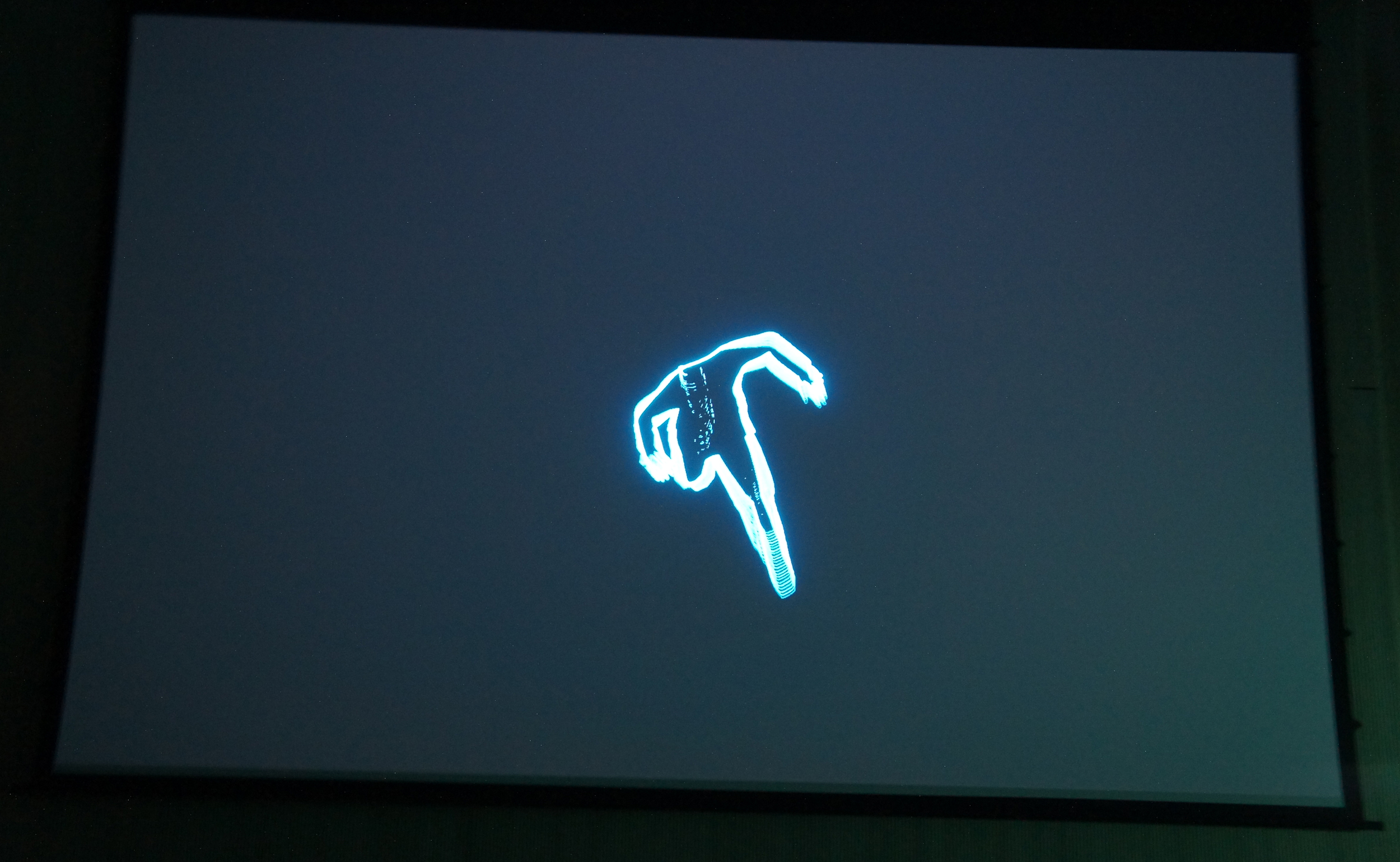

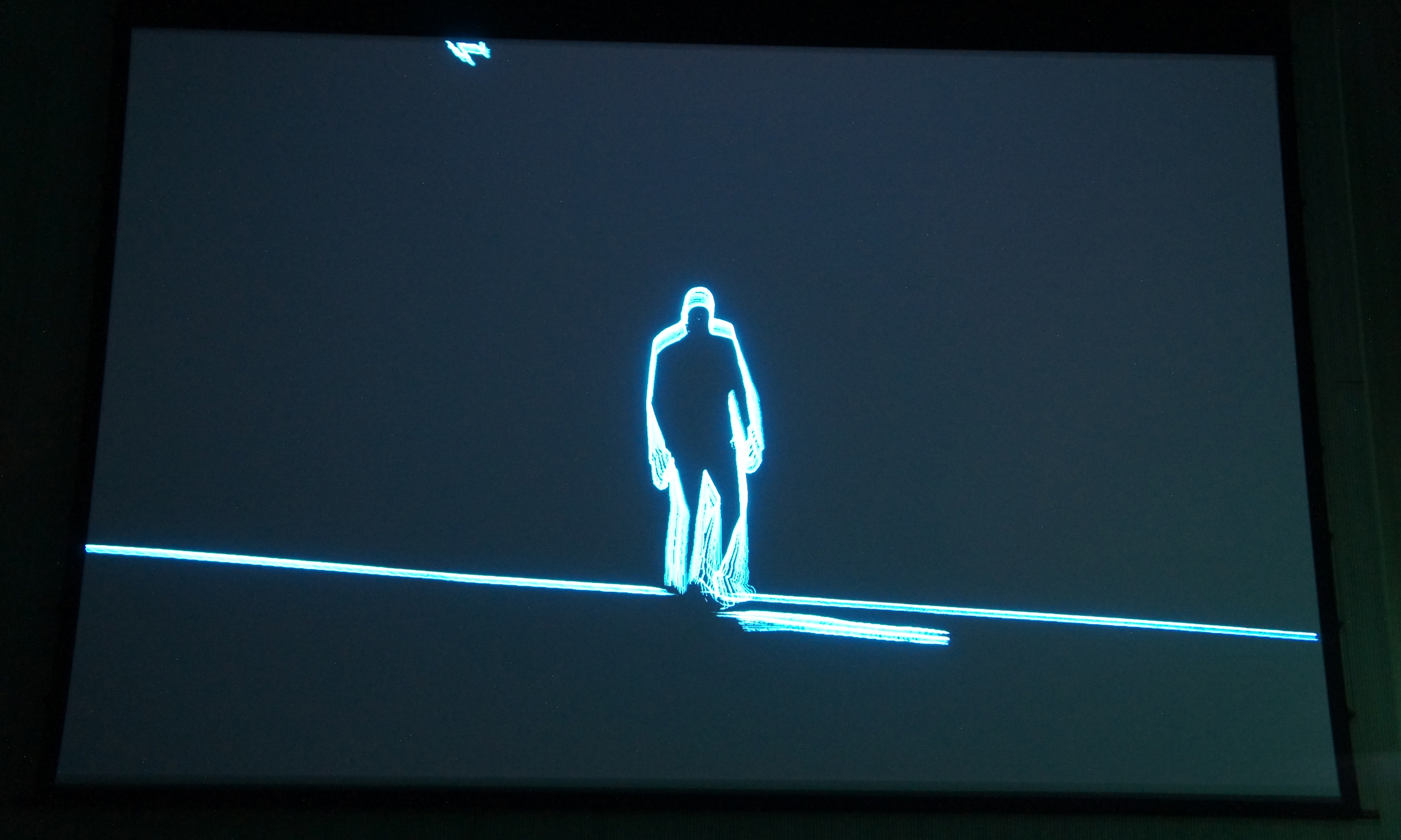

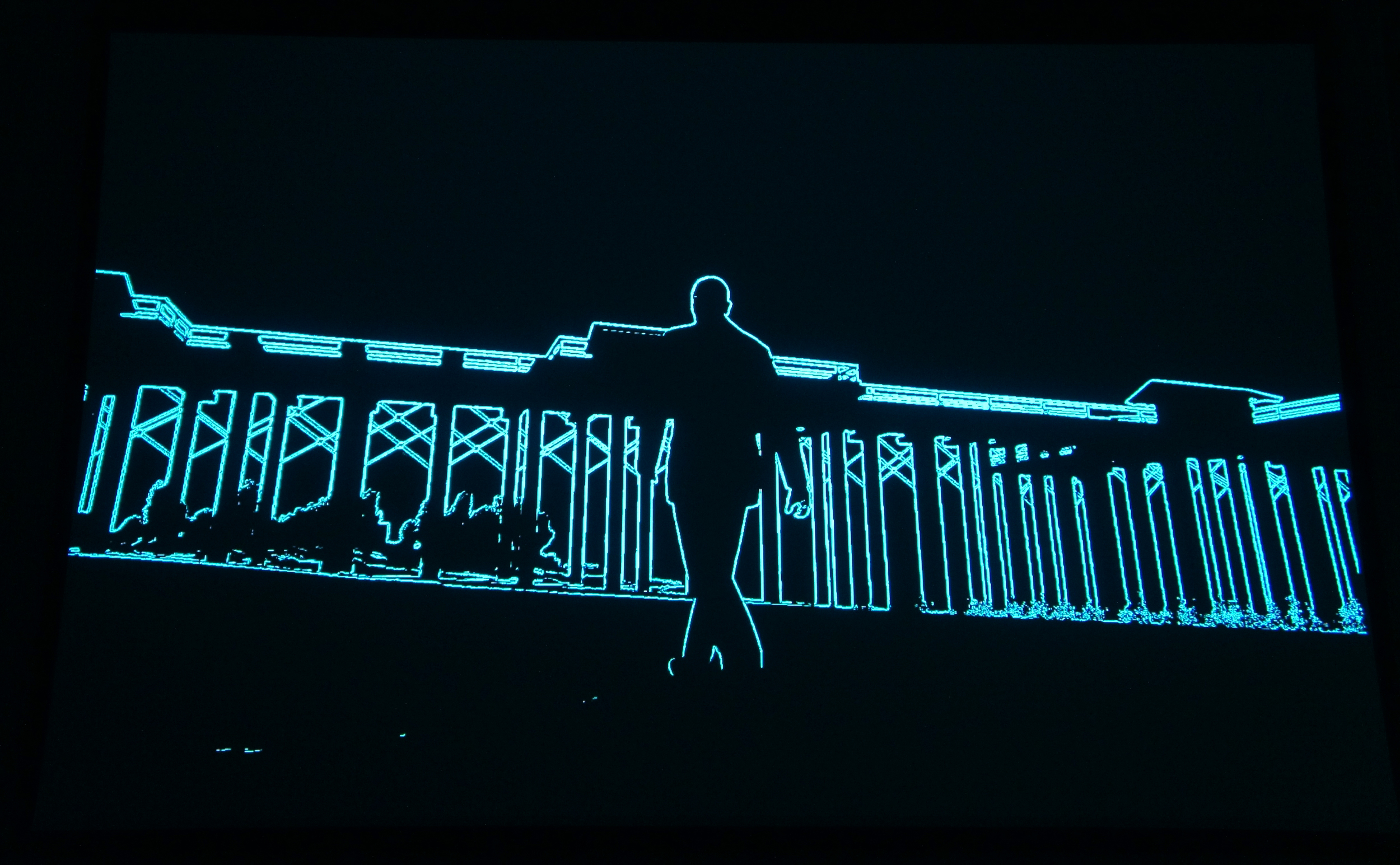

Brent Watanabe, San Andreas Deer Cam, 2016. Still from installation.