EVENT: CATALOGUE PRESENTATION (THURSDAY, JUNE 30 2016, 3.30 PM)

WHAT: CATALOGUE PRESENTATION

WHEN: THURSDAY JUNE 30, 2016, 3:30 PM

WHERE: SALA DEI 146, OPEN SPACE IULM 6

FREE ADMISSION & OPEN TO THE PUBLIC

DESCRIPTION

Published by Silvana Editoriale, the official catalogue of GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY will be introduced by a panel comprising Andrea Cancellato, (Triennale CEO), Prof. Mario Negri (Rector), Prof. Gianni Canova (Pro Rector), and Matteo Bittanti (co-curator). The book was edited by Matteo Bittanti and Vincenzo Trione and features contributions by Claudio De Albertis, Mario Negri, Vincenzo Trione, Vanni Codeluppi, Anna Luigia De Simone, Stefano Bartezzaghi, Isabelle Arvers, Henry Lowood, and Matteo Bittanti. In addition, the catalogue includes quotes from the artists' interviews produced by the Master's Degree students in Arts, Cultural Heritage, and Markets at IULM.

The presentation will be followed by a performance by artist Marco Mendeni (Sala dei 146, IULM 6) entitled r lightTweakSunlight01.

COSA: PRESENTAZIONE CATALOGO

QUANDO: GIOVEDì 30 GIUGNO, ORE 15.30

DOVE: SALA DEI 146, OPEN SPACE IULM 6

INGRESSO LIBERO E APERTO AL PUBBLICO

DESCRIZIONE

Pubblicato da Silvana Editoriale, il catalogo ufficiale di GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY sarà introdotto da un panel formato da Andrea Cancellato (Direttore Generale, Triennale Milano), il Rettore Mario Negri, il Prof. Gianni Canova e Matteo Bittanti. Curato da Matteo Bittanti e Vincenzo Trione, il volume include contributi di Claudio De Albertis, Mario Negri, Vincenzo Trione, Vanni Codeluppi, Anna Luigia De Simone, Stefano Bartezzaghi, Isabelle Arvers, Henry Lowood, Matteo Bittanti, nonché citazioni tratte dalle interviste agli artisti realizzate dagli studenti della Laurea Magistrale in Arte, Patrimoni e Mercati della IULM.

La presentazione sarà seguita da una performance dell'artista Marco Mendeni intitolata r lightTweakSunlight01 della durata di circa 30 minuti, sempre in Sala dei 146.

Kent Sheely, Zappers, 2012

INTERVIEW: KENT SHEELY

IN THIS EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW, AMERICAN ARTIST KENT SHEELY DISCUSSES HIS PRACTICE WITH VIDEO GAMES, BEING AT THE MERCY OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN BIG CITIES, AND THE DEMOCRATIZING EFFECTS OF MACHINIMA.

Kent Sheely (b. 1974, United States) is a new media artist based in New York City. His work draws both inspiration and foundation from the aesthetics and culture of video games, examining the relationships between the real world and virtual ones. Much of his work centers around the translation and transmediation of symbols, concepts, and expectations from game space to the real world and vice versa, forming new bridges between simulation and reality.

Kent Sheely's installation READY FOR ACTION (GRID, SECOND VERSION) (2013) is on display in the ASSEMBLAGE level of GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY.

This interview was produced by the students of Master's Degree Program in Arts, Markets and Cultural Heritage at IULM.

GVA: Can you briefly describe your education?

Kent Sheely: I initially went to school as a graphic designer, but after three years of studying the requisite art history and learning the tools of the trade, I realized I was absolutely not on board with the kind of rigid structure I was heading toward and migrated into a more organic, concept-driven area of study instead. I started reading about early performance and video art, and some of the people who were already experimenting with digital media and video games as a medium, and quickly decided that was where I needed to be.

GVA: Can you name some influences - not necessarily artistic ones - that played a key role in your evolution as an artist?

Kent Sheely: I think the first real influence on my own work was Red vs. Blue, a web-based show that was filmed entirely within the game Halo. It was my introduction into the concept of Machinima, the process of constructing narrative within video games. Of course I wanted to move beyond the classical structure that show worked within, but it was definitely a key factor in my early progression as an artist. I also did a lot of research into the artists who were already working in similar ways, such as Aram Bartholl, Brody Condon, Mariko Mori, and so many more. I really wanted to contribute my own voice to this rapidly-evolving scene.

GVA: When and why did you begin using video games in your practice?

Kent Sheely: As I mentioned before, I didn’t start using games to make art until I was in college. I was already obsessed with video games, and I wanted to essentially validate all the time I was spending playing games by using them as a tool to say something meaningful. I started out making work that either served as love letters to games or just used them as tools for creation, but as years have passed I’ve started getting much more critical toward the medium itself, incorporating themes of politics and institutionalized violence into the underlying themes of my artworks.

Kent Sheely, dust 2 dust, 2012.

Two teams of weapons battle for control of a small Middle Eastern town in Counter-Strike: Source.

GVA: Why did you specifically choose a video game to make art? What do you find especially fascinating about this medium? Its interactivity? Agency? Aesthetics? Theatricality?

Kent Sheely: I think I’ve created work that touches on all of these over the years! Game-based art pulls from traditions of appropriation, interactive media, video, photography, and more than I can possibly detail. Games are an endless playground of possibility.

GVA: The creative opportunities afforded by machinima are greatly constrained by existing copyright law, which prohibits many possible uses, including commercial purposes. What’s your take on the paradoxical nature of this artform?

Kent Sheely: This is a subject that actually comes up a lot, and I’m not sure how things are in other countries, but at least in the United States the appropriation of video games is covered by the Fair Use copyright law. That’s how properties like Red vs. Blue have been allowed to exist and make a profit. This means that as long as you’re adding commentary to the material you’re using, creating a parody, or manipulating the original material to a sufficient degree, you’re free to do what you wish with the source. Regardless of the way the law sees machinima, I like to think of it as an inherently subversive act, especially when used to comment on the subject matter in the game being used.

GVA: Would you agree that machinima has democratized the art making process? Has it lowered the entry barrier for creators of video art, as some critics argue?

Kent Sheely: The tools that have been developed in recent years for creating machinima have brought it into the mainstream consciousness & made it easier for people to use for their own creations. Resources like Source Filmmaker have made it easy for even children to craft their own stories using their favorites games. I definitely don’t see this as a bad thing, even though the medium is now flooded with an overwhelming amount of very poorly constructed works; I see it as an opportunity for more people to become aware of video games as a valid medium, and more diverse voices to be added to the conversations that have been happening for years now.

Three Experiments in Virtual Photography by Kent Sheely SITUATION #34: http://situations.fotomuseum.ch/portfolio/kentsheely/ Interview by Marco De Mutiis, fotomuseum, Winterthur, 2016

GVA: How do video game aesthetics affect the overall impact of your work? What comes first, the concept or the medium?

Kent Sheely: My creative process almost always involves playing games, and the work emerges from my experience of looking at them from different points of view. For example, Ready for Action emerged from playing Grand Theft Auto IV while I lived in New York City, where the game is set, and realizing how vastly different my experience of the city was from the main character’s. He is in no way bound by the constraints of a normal citizen; he doesn’t have to wait for buses or trains or taxis, because he’s afforded the freedom to just steal cars & mash the gas pedal until he gets where he wants to go, ostensibly without consequence. The game expects this of him, and expects he will enact any violent means necessary to realize this potential. I found a lot of joy in forcing him to take the long way round, living as an ordinary citizen even though he still carries an automatic weapon around everywhere he goes, a visible reminder that he’s doing something wrong as far as the game’s framework is concerned. This is how most of my work develops, through play.

Kent Sheely, Ready For Action #10, 2016

This is part of an ongoing series of scenes featuring video game characters at the mercy of public transportation. Audio from the game has been blended with audio captured while waiting for public transportation in the real world.

GVA: What kinds of games have you selected to create Ready for Action?

Kent Sheely: When making a new iteration in Ready for Action, I primarily look for games that feature some form of public transit as a set piece, but more specifically I seek out games that try to emulate the way those spaces look and feel in the real world. They’re generally pre-populated with stationary characters whose only purpose in the game is to look like they’re waiting to be picked up, or at least built to look like they are in operation. As the main character, I try to blend into this setting as best I can. A lot of games also feature an “idle animation” that makes it look as though your character is growing impatient, which always makes it look that much more authentic when I’m simply standing around at the mercy of a force I can’t control, yet wielding an incredibly dangerous weapon that I could use at any time to inflict my agency on my surroundings, yet I don’t.

Kent Sheely, Ready for Action #9, 2015

Part of an ongoing series of scenes featuring video game characters at the mercy of public transportation. Audio from the game has been blended with audio captured while waiting for public transportation in the real world.

GVA: Ready for Action can be considered as a kind of Waiting For Godot 2.0. Do you think there is a parallel between the exhausting and unsettling urban wait of your characters and the real and dreadful one lived by a soldier waiting for battle?

Kent Sheely: Although there are weapons featured in Ready for Action, I try to disconnect the characters as much as possible from the idea of combat and violence, and instead let the weapons represent agency and the ability to take action, which my character clearly does not employ. In that sense I suppose the connection to Waiting for Godot is appropriate, as the main character’s purpose of existence is inevitably called into question. If you take away a game character’s freedom, what’s the point?

Read more interviews here

kentsheely

INTERVIEW: MARCO MENDENI

In this exclusive interview, Italian artist Marco Mendeni talks about video game epiphanies, creating machinima, and living in Berlin.

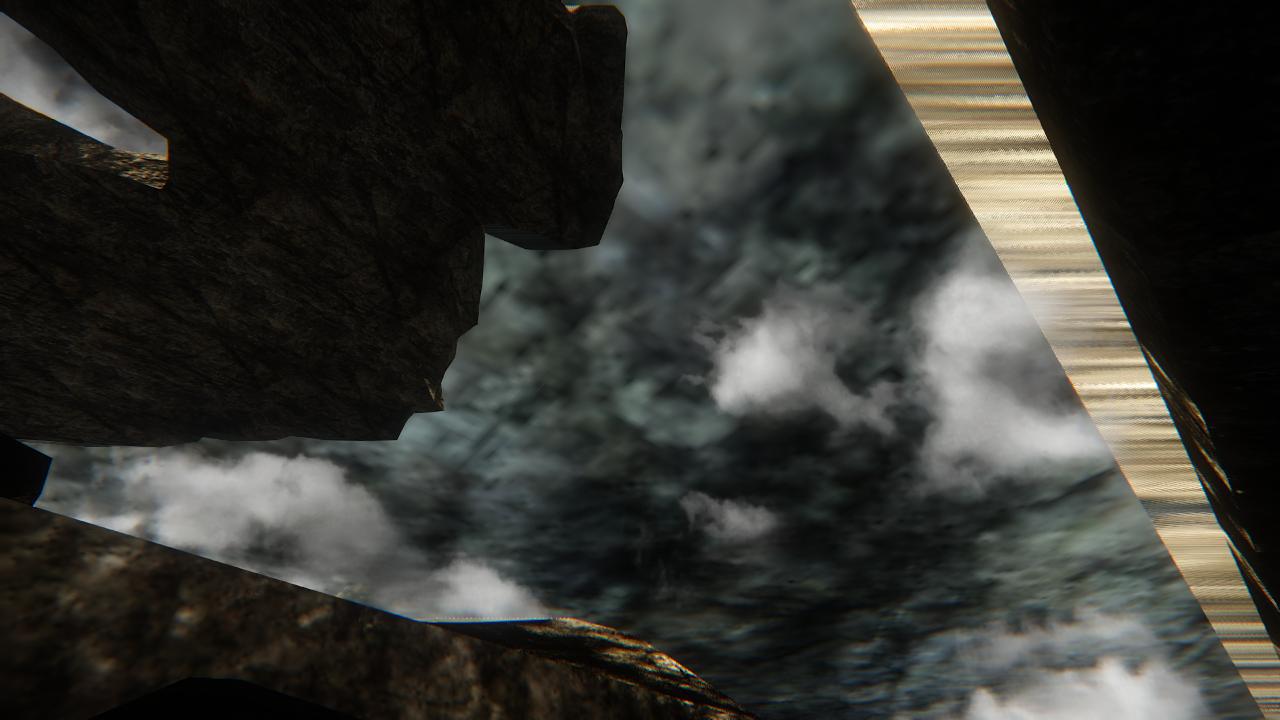

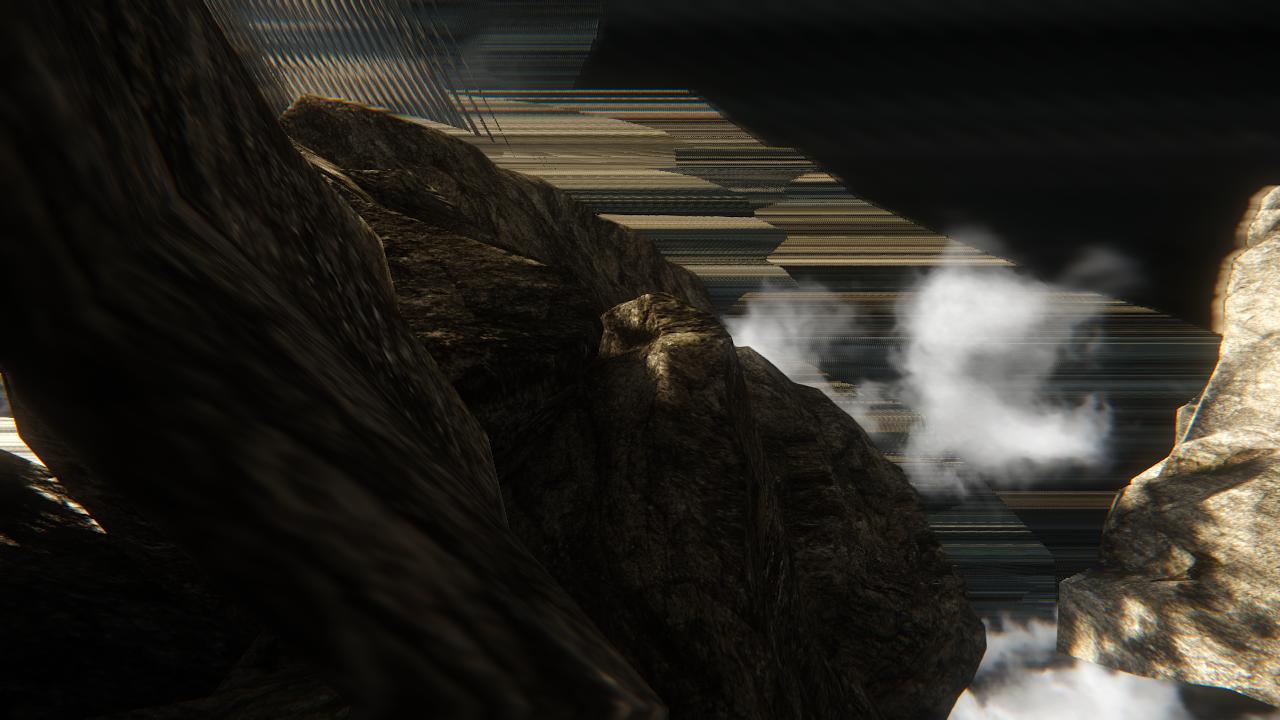

Marco Mendeni's r_lightTweakSunlight01 is currently on display in the GLITCH level of GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY.

This interview was produced by the students of Master's Degree Program in Arts, Markets and Cultural Heritage at IULM.

GVA: Can you briefly describe your education?

It all began in my father’s studio. I still remember the plaster and the smell of glues for the frescoes… These materials that would mutate into something else was my first true artistic experience. Then, I studied painting at the Accademia di Brera in Milan. My clothes were always stained with paint. Suddenly, I dropped everything and I stopped my painting practice. One day, though, I had an epiphany. I blame an old iMac, a digital piano, a Sony PlayStation 2, and a JVC mini DV camera. I was living in a small flat in Brianza with my current partner. It took us days to finish Alien Hominid in co-op mode. Then I enrolled in the New Technologies for Art Program at Brera.

GVA: Can you name some influences - not necessarily artistic ones - that played a key role in your evolution as an artist?

Marco Mendeni: Alan W. Watts, Marcel Duchamp, long sessions at Resident Evil 2, Jean Baudrillard, a Joan Leandre’s exhibition at DAM Gallery in Berlin, all those nights spent recording and watching crazy dudes on PlayRoom, Techgnosis on my bedside table for months, Ryoji Ikeda, Mario Canali’s classes, I Ching, Nam June Paik, Tarkovskij’ Nostalghia in a classroom at Brera, in the middle of July with Franco Baresi, Marshall McLuhan, Sao Paolo’s surveillance and security systems , my conversations with Paolo Rosa about video games, spending whole days in an internet café in the Turkish district of Berlin surrounded by kids swearing in unintelligible languages while playing Warcraft and many more things…

Live gameplay extract from "I'm not playing", audiovisual performance for hacked video game and real-time sampler. Video: Marco Mendeni Sound: Bob Meanza

I’m not playing is an audiovisual performance that talks about the relationship between the videogame medium and the culture of simulation in the digital era. Through the years, video games have influenced our perception of space/time and our concept of identity, and we have now reached a point where real and virtual worlds are merging their borders. In this process, the videogame as a container of ideological power cannot be underestimated. I’m not playing addresses all this through a war videogame played every day by millions of people: COD4. During the performance, COD4 is played in real time, but the visual and sound landscapes of the game are transformed. Thanks to a hack of the graphic engine, the game shows us real and virtual battlefields at the same time, fragmented among islands of disturbing hypnotism. The audio track is also de-structured in real time, through a script that assigns new sounds to the original sound effects, which is controlled live during the performance.

GVA: When and why did you begin using video games in your practice?

Marco Mendeni: At one point, painting became boring for me. When I discovered video games and new media in general, I experienced a sense of excitement and rapture that I had not felt in years.

Marco Mendeni, FOV 1, 2012, installation view

GVA: Why did you specifically choose a video game to make art? What do you find especially fascinating about this medium? Its interactivity? Agency? Aesthetics? Theatricality?

Marco Mendeni: More than any other medium, video games allow us to live an artificial reality: this is the aspect that truly fascinates me. Videogames are extraordinarily malleable because they are constantly evolving and, over the years, they have appropriated the features of other media and somehow reinvented them all. Thus, video games are a kind of meta-medium. Consider the imminent introduction of virtual reality displays like the Oculus Rift et similia. How they will affect our understanding of the world? Will we get used to live in another reality? I find this possibility both terribly exciting and scary at the same time. It looks like we are headed in this direction, that is, coexisting in multiple planes of reality. The video game - what a seemingly innocuous name! - is now becoming quite real… A few years ago Facebook seemed a fun thing to do but today we recognize it for what it truly is: a monstrous mechanism. I wonder if the same will happen with video games…

MENDENI'S NOT PLAYING GAMES. FOR REAL. Short critical video by Matteo Bittanti, 2013

GVA: Digital games often create parallel, alternative experiences for its users. How do you relate to the complex relation between reality and simulation? How do you address this tension through your work?

Marco Mendeni: The fulcrum of my artistic practice is a careful study of the parallels between reality and simulation. This is a very complex issue. The truth is that we were unprepared for the technological transformations that we unleashed. Thus, our biological failure forced us to build a tailor-made world. Reality and simulation have become an integral part of ourselves. This is what fascinates me the most ... In short, this process of constant reinvention of reality is our history, our nature.

Marco Mendeni, CimSity, digital processing on concrete, 2013

GVA: Do you agree that machinima has democratized the art making process? Has it lowered the entry barrier for creators of video art, as some critics argue?

Marco Mendeni: Definitely. Any artist is often faced with an insurmountable obstacle: the economic cost of a new project. I hit so many brick walls in the past. But with machinima, all one needs is a personal computer, a game, and electricity. In this case, the true limit is not technical or pecuniary. The only limit is the artist’s imagination.

Marco Mendeni, FOV2, 2013